Sekiro:

A Ferryman to Nirvana

Abstract

Sekiro: Shadows Die Twice is FromSoftware’s 2019 addition to their SoulsBourne lineup of videogames. It follows the narrative of a young shinobi, Sekiro, bound to his master who will do anything needed to exercise his will. The game diverges from the typical Dark Souls strategy for a narrative told by deeply ambiguous lore which may go over players’ heads the first three playthroughs for a more traditional story. But unlike typical narrative games, Sekiro utilizes FromSoftware’s experience in crafting complicated narratives to underly a far more ambiguous fable of the teaching of Vipassana through elements of narrative such as the burdens of immortality, uses of game mechanics to teach patience, precision, and dedication, and imagery of East Asian religion to tell stories without needing to spell out the words. The protagonist Sekiro ends up heralding not only himself, but his master, antagonist, and the player into the game’s version of Nirvana, immortal severance.

Introduction

The waving of a hand back and forth offers a peculiar illusion, our brain is still comprehending the image being processed in front of it, thus holding a still frame for moments after the hand has already moved on; when stitched together these images form a blurred image in our mind. The question arises instantly, of what do we classify this blur as? Could it be the hand itself, in multiple places at once? Perhaps it is a single physical phenomenon undergoing various repeating stases? Vipassana meditations insist that at the understanding of this question is the key to a purified soul, that this answer, in tandem with Buddhism’s four noble truths, will lead to escape from the cycle of rebirth, and entrance to Nirvana. In FromSoftware’s 2019 title Sekiro: Shadows Die Twice, imagery, narrative, and mechanics are used as multi-facets to examine the philosophy of Buddhism, specifically to explain nuances and variability about the concept of enlightenment.

Representations of Buddhist Teachings

With the major plot of the game out of the way, we can begin to dissect the way in which, beyond the statues of the Buddha scattered throughout the game as decoration, the narrative and mechanics tell a hidden story below the surface, one of the Vipassana meditations.

To begin we will break down what immortality really is in Sekiro. First, we find a solution the question I posed you earlier. What should we think about the blur our hand leaves behind as it travels back and forth in front of our eyes? To answer, we can turn to the Dharma practice of purification (Kornfield, 199). This practice tells us that a yogi practicing Vipassana must first not only come to grips with the impermanence of the world, but also feel the impermanence throughout themselves. The Buddha spoke of physical and mental phenomena, which, in short, are bodily actions, and thoughts. These physical and mental phenomena are not set in place, in fact they are constantly changing, but beyond changing they are repeatedly vanishing and appearing. Going back to the hand question, the blur that is seen as the hand moves are not iterations of the hand itself, but rather separate physical phenomena. The hand that was once on the left is no longer, there only exists the hand that now resides on the right, and if the hand were to move back to the left, the reverse is said. In the purification there is no past or future, but only the present, the past has vanished, and the future has yet to appear. The original question ends up being the perfect analogy to visualize this concept, and can be used to contemplate the impermanence of self. With proper implementation and understanding of impermanence, ego and personality are destroyed, two important steps on the journey to enlightenment.

Immortality in Sekiro is the antithesis of purification. It is built to represent the desperate cling to self that comes with a rejection of the cycling nature of the physical and mental. When Genichirio reveals his immortality, he tells us.

“This land is everything to me. For her sake I will shed humanity itself.” This shedding of humanity refers to the separation of his mental and physical state his immortality has perpetrated. An immortal flesh paired with a mortal soul, permanently detached so long as he remains immortal. A similar phenomenon depicting the destruction of mind of body occurs to the monks found in Sekiro’s Senpou temple. Upon reaching the destination, a nearby tapestry depicting a practitioner of the Dharma tells us that the monks of Senpou temple, seduced by immortality, have given up their path to enlightenment to pursue permanent physical stasis. As Sekiro moves through the temple, the monks become more and more disfigured, growing centipedes from their mouths with skin decaying from their bodies. Yearning for stability from the volatile world they ruin their purification, resulting in unsatisfaction and suffering. They have given up the vanishing and appearing nature of the hand on a pendulum, instead they attempt to ignore their impermanence, clinging onto artificial immortality.

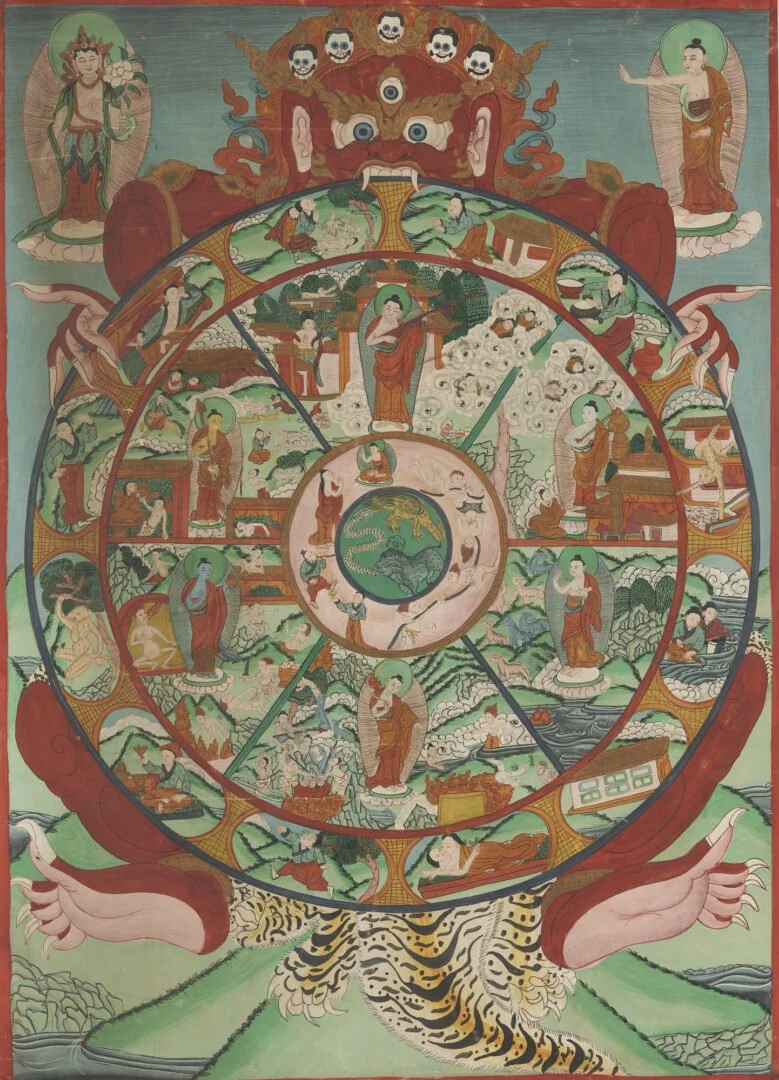

It becomes a trend to forgo authentic life to pursue an inauthentic escape from suffering. From this artificial escape breeds evilness from greed, hatred, and ignorance, three traits which contradict the Dharma’s message that “universal love comes from total unselfishness”(Kornfield, 14). No imagery within Sekiro makes this interpretation clearer than the Halls of Illusion. Within this subsection of the Senpou temple, the player is transported via meditation to a place described as somewhere between life and Nirvana. In this halfway point the unique encounter Folding Screen Monkeys are fought. This ‘boss fight’ can be better described as a puzzle, where the player must figure out ways to capture four monkeys running around the halls. Each has a unique trait which makes its capture fairly obvious: a green monkey, with excellent hearing can only be caught by ringing a bell while it stands nearby. A purple monkey, with perfect vision needs to be cornered into a dark room where it cannot use its enhanced eyesight. An orange monkey, who carries a pot and pan to warn the others when the player approaches can be forced into a room neighboring a waterfall, where nothing can hear the clanging over the sound of rushing water. And lastly is a white monkey, who follows the player around invisible, with only its footsteps visible. Each monkey represents the opposite of each of the four wise monkeys; those being, hear no evil, do no evil, see no evil, and speak no evil. Slaying these foes is the player rejecting each evil thought themselves and moves the player beyond the Halls of Illusion into an inner sanctum of the temple.

While this is an up-front interpretation, practically spelled out by the game, there is beyond, a deeper importance to this section. After talking to a monk found standing solemnly in the halls, he reveals his own fate, that he finds solace in his closeness to Nirvana, essentially giving up completely on the life defining purpose to seek true enlightenment. Beyond this, he tells a story of another who came through the halls, fruitlessly chasing the monkeys for a long time, before eventually falling silent. I argue this is the real reason for this room to be added, as a representation of the Buddhist teaching to not dwell on evil thoughts. The constant chasing of these monkeys which represent the evils themselves is the inability to truly let them go, it is only through capturing them can you release the evils, and sincerely speak, hear, see, and do no evil.

Conclusion

Sekiro: Shadows Die Twice takes its players on a complicated narrative through a challenging game, carefully crafting an experience embodying the teachings of Vipassana. Sekiro himself comes to accept impermanence and finds his path from sufferings and desire, emulating the path to enlightenment. The player follows the journey alongside the characters, game mechanics such as the revival system paired with the give and take timing-based combat guide the player through a learning curve meant to replicate the same journey through the Four Noble Truths. The world it littered with clues to follow on the hidden meaning behind the game, which in typical FromSoftware fashion, can only be put together if it is being actively sought out. An in-depth analysis isn’t required to understand the story of the game, but to truly get out from the game what is meant to be extracted, such analysis is necessary. With such dissection this narrative becomes far more meaningful, and makes they player feel like they have accomplished something beyond just the completion of another game.

Context

Sekiro takes place during the latter half of Japan’s Sengoku period, where warlords rise from every corner of the nation to jockey for control. Blood, razed villages, and dismantled shogunates have become as common an occurrence as a harsh crop season. During this era, no ground to stand on is stable, and power seeps as water through cupped hands. A second of stability has become as valuable a commodity as gold, leaving rulers grasping at anything they can to balance themselves, and regain a mimicry of power.

The power struggle manifests itself as the antagonist Genichiro, and is seen scattered throughout the lands. Genichiro, the adopted son of Isshin Ashina, a sword saint inspired by the legendary Japanese swordsman Miyamoto Musashi, rules at the head of the Ashina clan, desperately trying to hold together his families lands through any means necessary. He has kidnapped the protagonist Sekiro’s master, Kuro, intending to use Kuro’s unique blood to grant himself immortality. The narrative follow’s Sekiro’s quest to reunite himself with Kuro, and stop Genichiro’s plot.

The first third of the game guides a very straightforward narrative of the hero on a mission to save their damsel in distress, cutting through foes to reach Ashina castle. Throughout this section of the game the unique connection between Sekiro and Kuro is unveiled. Sekiro has devoted himself completely to the protection of his master, and in doing so has been given by Kuro a sample of his blood. Kuro, cursed with the Dragon’s Heritage, is condemned to a life of immortality which can be shared through his blood. When death befalls Sekiro, a second chance is given, with Sekiro able to rise where he fell, turning him into an unstoppable force dedicated to serving his master.

After a journey through the outskirts, and up the levels of Ashina Castle, Genichiro and Sekiro face of in a duel. Sekiro strikes down Genichiro, but to his surprise Genichiro rises from the ground, revealing that he has bathed in the sediment within the rejuvenating waters, granting his physical form immortality. The duel concludes with Genichiro retreating from his castle, where Sekiro is reunited with his master. From this point the true story is revealed, Kuro asks Sekiro to figure out how to severe his ties with immortality, so that the Dragons Heritage can finally come to an end.

Four Noble Truths

The combination between a surrender of evils and the disposition of self and ego makes up half of Vipassana meditation’s criteria for an enlightened soul. The missing piece is the relationship between one’s person and the Four Noble Truths (Kornfield, 316). These truths are fundamental aspects to the teaching of the Buddha, and within Sekiro they are traced as paths taken by the three key characters in the fiction. Those being the paths of Sekiro, Genichiro, and the player themselves.

Dukkha: life is suffering. Sekiro is found alone, a child, with nothing to stand on, and taken in as a shinobi. He is raised to follow the Iron Code; to above all else follow the word of his father. He is given the task to protect his master Kuro at whatever cost, stripped of his agency Sekiro lives for nothing beyond the word of his master or his father, with failure being a worse option than death. On the opposite end of Sekiro is Genichiro, the leader of his clan with his family heritage delicately resting in his hands. His land is burning and his people are dying, his complete agency and fear of failure causes him great suffering. While the player is unraveling the story they are faced with a frustratingly difficult game, one that is ruthlessly unforgiving where the smallest mistakes result in failure. Even the earliest stages of the game leave the player wanting to quit.

Samudaya: the cause of suffering is clinging and desire. Sekiro finds himself in a paradox when Kuro asks for him to sever his immorality, the Iron Code tells Sekiro he must obey his master and let no harm befall him, thus, to be asked to find a way to kill Kuro puts him directly in a contradiction. Sekiro clings to his Iron Code, but desires nothing more than to serve Kuro. Genichiro’s craving of control results in his decision to bathe in the rejuvenating waters, permanently separating his immortal flesh from his mortal mind, his greed slowly tearing him apart at the seams. Combat in Sekiro is a game of give and take, relying on the rhythm of the player to know when to strike and when to parry, without patience the player overextends, resulting in nothing but frustration.

Nirodha: the truth to end suffering is to end desire. To escape suffering Sekiro must forgo the Iron Code, give up all he knows and show humility to his master. Through universal love and unselfishness, he can help Kuro, and break himself free from the paradox the code has him trapped inside. Genichiro’s path away from suffering can only be completed by giving up is attachment to Ashina, to reverse his immortality and accept the collapse of his shogunate. The player must come to grips with failure, learn from mistakes, and give up the desire for instant gratification. They need to embrace reaction over action in combat, and not force the game to be something it isn’t.

Marga: There is a path that can be taken to lead away from desire and suffering. The path comes together for Sekiro in three possible endings of the game. The first he successfully gives up his code, and follows through with Kuro’s orders to kill him, cutting off the Dragon’s Heritage and ending Kuro and Sekiro’s immortal bond. The second follows closely with the first,

but rather than kill Kuro, Sekiro ends his own life, resulting in the same outcome as previous. The final and often regarded as the true ending to the game, Sekiro choses to neither kill himself nor Kuro, to instead delay their own entry into Nirvana to unravel the secrets of the Dragon’s Heritage, to hopefully save others who may be in similar situations. In this truest ending Sekiro follows the path of the Bodhisattva, Avalokiteshvara, a figure in Buddhist religion known for their infinite compassion and mercy. Avalokiteshvara had reached complete detachment and were prepared to sever their ties from the cycle of rebirth, but rather than reaching Nirvana, they postponed their entrance upon seeing the thousands of people suffering. They chose to delay their enlightenment to help those suffering find their own path into Nirvana. This act was seen as the highest possible form of compassion (Bodhisattvas). Just as Avalokiteshvara did, Sekiro sets aside his enlightenment for the sake of others.

Genichiro’s conclusion comes just prior to Sekiro’s own. In the final showdown of the game, a duel between Genichiro and Sekiro seals his fate, with Sekiro severing Genichiro's immortality a final time using his Mortal Blade*, conjoining his mental and physical self once again, allowing him to die in satisfaction, ending his suffering. During this final duel the game presents the player with its hardest challenge yet, a four-stage fight that tests every fundamental the game has been teaching them along the way, timing is incredibly precise, mistakes are punished in a practically unrecoverable way, and insurmountable patience and concentration are pivotal to success. To succeed the player needs to be completely unselfish, any amount of impatience results in failure, only through near perfection can victory be achieved.

Bibliography

Evans-Wentz, W.Y. The Tibetan Book of the Great liberation. Kathmandu: Pilgrims Publishing, 1999.

Kornfield, Jack. Living Dharma. Boston: Shambhala Publications, 1996.

SocraTetris. “Mortal Ethics of Sekiro | Philosophy of Games | From Software.” Youtube, May 1, 2020. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZDFhIghnOVs

University of Washington. “Bodhisattvas.” Accessed May 25, 2023.

https://depts.washington.edu/chinaciv/bud/5imgbodd.htm

Writing on Games. “Examining the Themes and Story of Sekiro: Shadows Die Twice.” Youtube, April 1, 2019. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZIEoeUy8KH4